Greenway is situated on the edge of the River Dart in Devon. Agatha Christie (1890-1976), Greenway's most famous occupant, called it the ‘loveliest place in the world'.

Agatha grew up in nearby Torquay and bought Greenway as her holiday home, spending summers here with second husband Max Mallowan (1904-1978) and daughter Rosalind (1919-2004) who came to live at Greenway after Agatha’s death.

One thing that can safely be said about Agatha and her family is that they were a family of collectors. Today, visitors to Greenway can see every corner filled with collectables – books, ceramics, Tunbridge ware, silver, textiles and more. Agatha even laments this in her 1977 autobiography saying 'there is no doubt that we were a family of collectors and that I have inherited these attributes. The only sad thing is if that if you inherit a good collection of china and furniture it leaves you no excuse of starting a collection of your own.' [1]

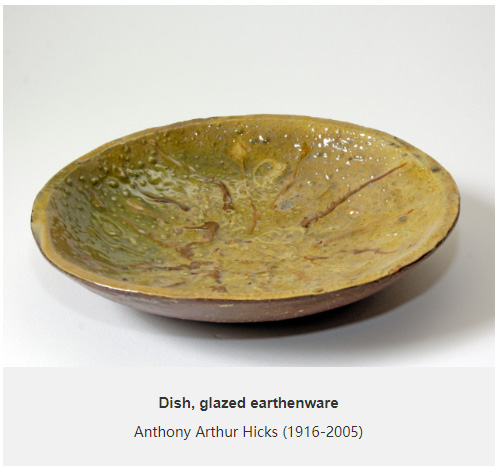

The ceramics collection in particular offers a great insight into the family and their collecting habits. Influenced by earlier generations, some of the inherited items that Agatha mentions belonged to her father Frederick Alvah Miller (1846-1901) whose collection of European porcelain came to Greenway. After her death, Agatha’s daughter Rosalind and her husband Anthony Hicks (1916-2005) also added to the collections extensively, particularly with ceramics.

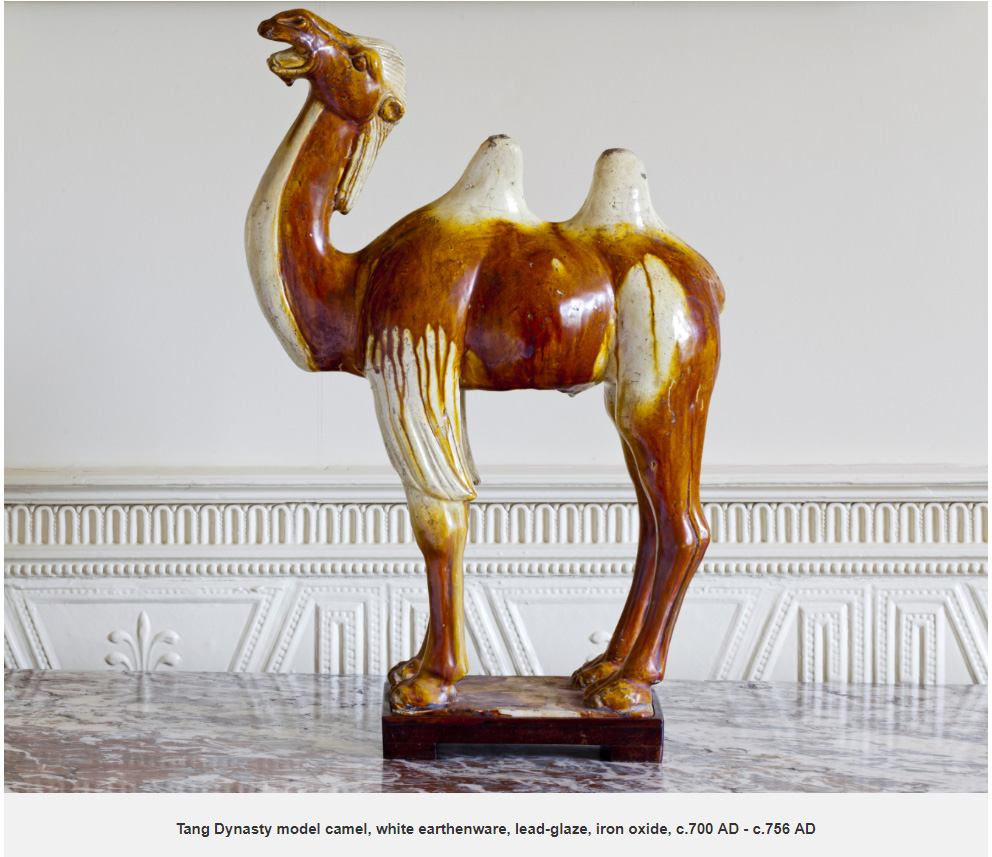

The multiple generations of collecting represented at Greenway are a fascinating insight into the tastes and collecting (or consumerist) habits of an upper middle class family. Rather than a conscious effort to acquire rare, valuable or connoisseurial collections, the family appeared equally interested in collecting ‘sets’ or multiples of relatively low cost items. The collection at Greenway ranges from ceramic treasures like the Tang dynasty camel to stacks of rather ordinary Ironstone china. Some pieces were collected for display in cabinets or on sideboards, whilst others – even some of the more precious items – were in common use. In addition, the studio pottery collection built up by Anthony Hicks is the only such collection in the whole of the National Trust.

Inheriting European Porcelain

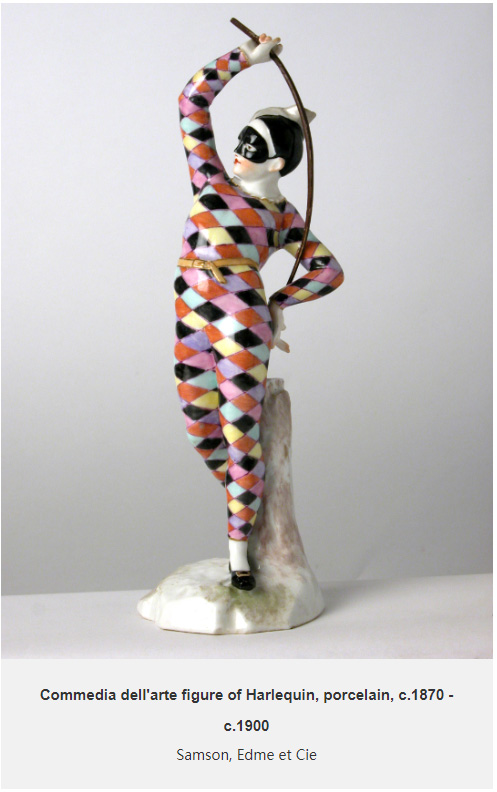

Agatha Christie grew up at Ashfield in Torquay surrounded by her grandparents' and parents’ collection of ‘China’. In her autobiography, Christie writes 'Grannie brought her collection of Dresden and Capo di Monte to Ashfield and cupboards were full of it.' [2] When Ashfield was sold in 1938, much of this came to Greenway and Agatha had to have new cupboards built to store it all. The family seemed to love ornamental figures, with many pieces coming from Germany (Meissen and Dresden), France (Samson), Italy (Capo di Monte) and also some from England (Crown Derby.)

Agatha’s father, Frederick Miller, was an American former partner of a New York department store and purchased a lot of German porcelain. He wasn’t interested in collecting the very early and incredibly rare pieces of German porcelain, however. Rather, he preferred to purchase contemporary pieces, or copies of earlier figures, showing that his interest was in the delight of the objects, not their monetary or collecting value. Two of the largest and most striking pieces in the collection are a pair of ‘Schneeball’ (snowball) vases. Originally, these detailed vases were made in the 18th century at the prestigious Meissen factory in Germany, but the examples at Greenway are 19th-century copies made at the Samson factory in Paris.

Receipts for many items in the house still exist in the archive. In 1881, Miller paid £11 for a set of figures of ‘Comedy’ and the ‘Elements’. One can imagine a young Agatha being fascinated by these figures which perhaps accounts for her early interest in the characters of the commedia dell’arte and the possibilities they held for imagining stories and characters in her novels. A Samson figure of ‘Harlequin’ is said to have been her inspiration for the series of short stories published in 1930 under the title The Mysterious Mr Quinn in which Mr Quinn appears ‘by some curious effect of the stained glass…to be dressed in every colour of the rainbow' [3].

Agatha and Max

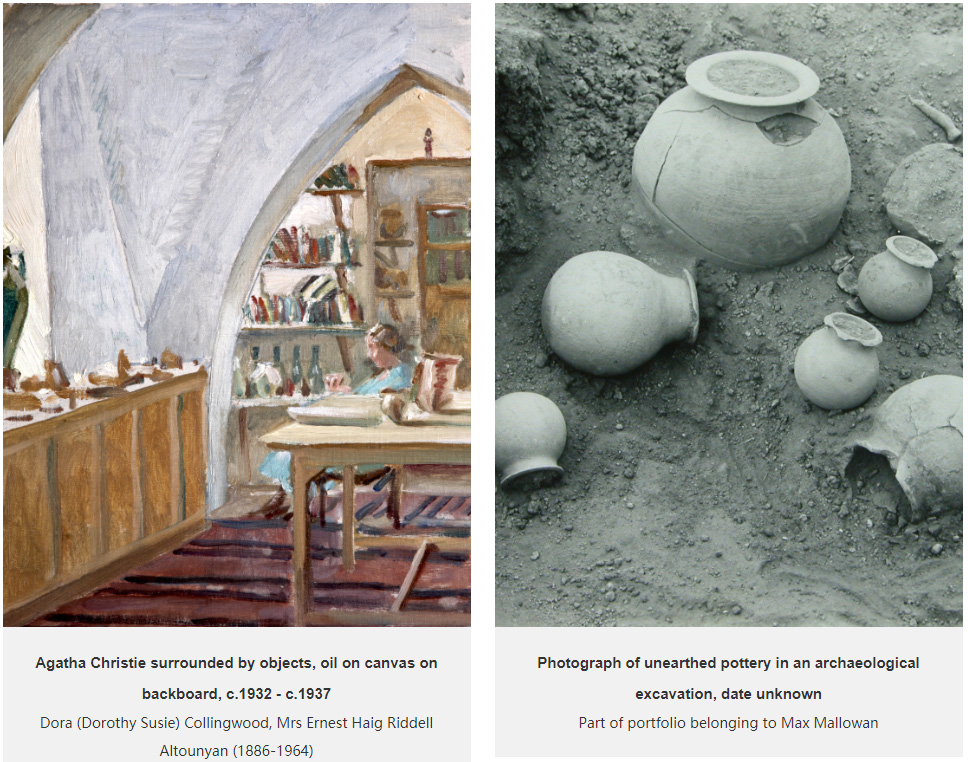

Max Mallowan (1904-78) was Agatha’s second husband. They married in 1930 having met in Ur in Iraq where Max was a member of the archaeological team and Agatha became a visitor and guest of Leonard Woolley, the expedition lead. We know from Agatha’s autobiography and from Max’s memoirs that ceramics were of particular interest to both of them. Agatha took up drawing lessons to record many of the ceramic finds and was a fan of the ‘brilliant colours’ of the glazed fragments. Between 1932 and 1937, Agatha spent some time in Chagar Bazar (northern Syria) where Max was working on another excavation. She was known to have repaired some of the ceramics that Max excavated. A painting on display at Greenway by Dora Collingwood shows Agatha surrounded by pots and, as Max described her there, ‘looking a picture of happiness' [4]. Max himself took a special interest in archaeological ceramics, using them to establish chronologies.

This interest also extended to Chinese items. Perhaps the single most important object at Greenway is a stunning Tang Dynasty earthenware camel. A gift from Max to Agatha, it was originally kept at their Winterbrook house before moving to the bedroom at Greenway. Today, it is on display in the dining room.

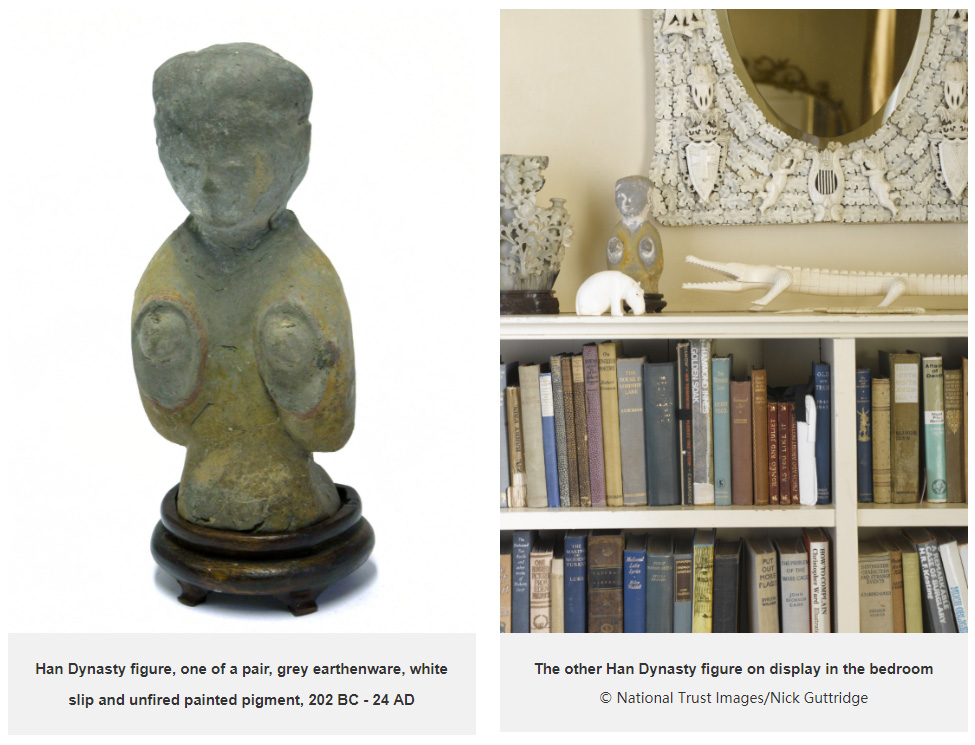

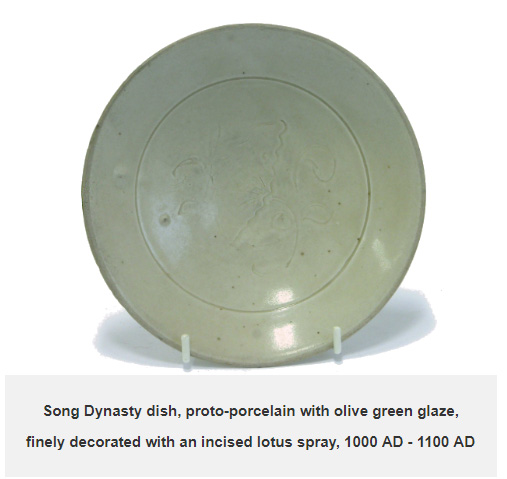

Around the house other items of Chinese porcelain can be seen, including some pieces of export Blue and White as well as rarer items such as a pair of Han dynasty figures. Max and Agatha lived with these items, understanding their importance but not always worried about keeping them under lock and key. They even purchased a Song dynasty dish to serve rice from, much to the dismay of the Oxford dealer from whom they acquired it. [5]

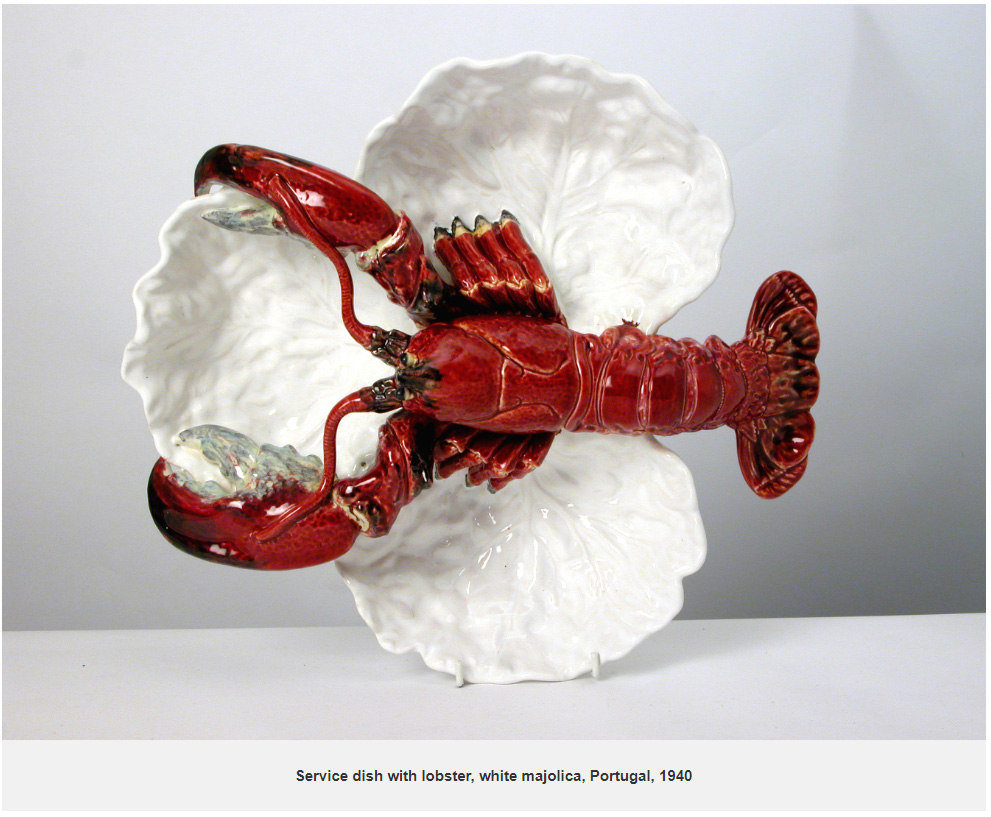

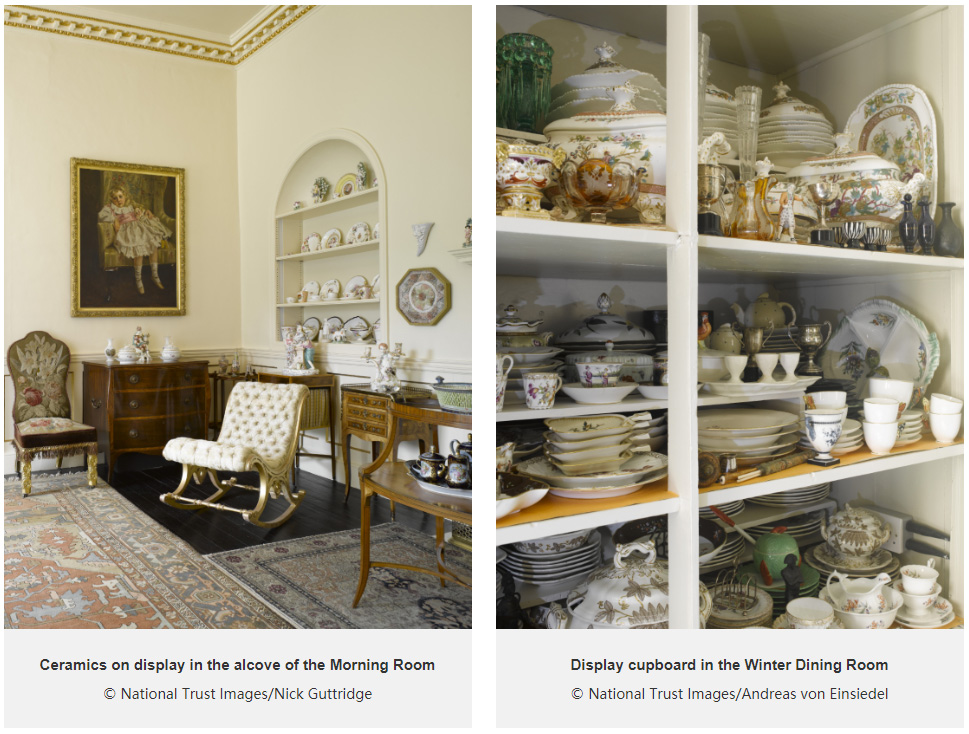

Other items at Greenway reflect the extent of Agatha’s travels; a lobster serving dish, popular with visitors today, was made in Portugal. (Lobster, incidentally, was Agatha’s favourite food followed by blackberry ice which she served at Greenway on both her 70th and 80th birthdays.) The extensive though often curious tablewares at Greenway, much of which were inherited from Agatha’s mother who was famed for throwing large dinner parties, are displayed packed into cabinets in the winter dining room. Domestic pottery sets with more modern designs crept into the collection, purchased from homestores such as John Lewis.

English pottery

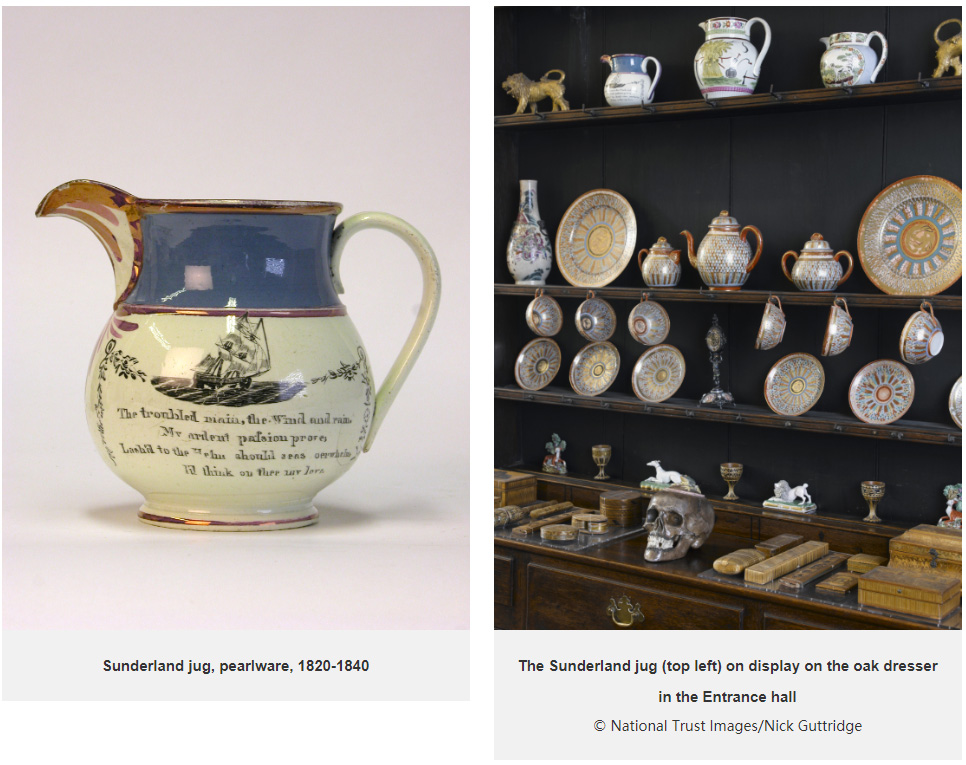

English pottery, much of which dates to the 18th century, also forms part of the collection that was certainly at Greenway by the 1940s. The variety of English pottery bears relation to the collecting approach applied to much of the rest of the collection; some pieces are rare, many are common. Some are decorative figures displayed in cabinets, others are tablewares purchased for use. Examples such as the Sunderland jug, which bears the inscription 'The troubled main, the Wind and rain / My ardent passion proves / Lashed to the Helm should seas oerwhelm [sic] / I'll think of thee my love', appeals to sentimentality but perhaps was collected with anthropological interest.

Transfer printed items show a political interest as well as cultural commentary. A creamware cup and saucer with portraits of George Washington and the inscription ‘our country’s father’ date to the 1780s when British potteries started to make wares for the American market - potentially of interest to Agatha’s American father. Another, dating to the 1770s, is a creamware mug printed and hand painted with ‘The Tithe Pig’ after an engraving by Louis Philippe Boitard which provided a commentary on the contentious practice of church tithes.

Max also chose to collect a large amount of pottery known as Bargeware (or Measham ware). It was made around Burton-on-Trent though largely sold at a shop in Measham which happened to be by the canal. This kind of ware was favoured by barge and narrow boat owners for its practical and decorative nature. The relative inexpense of this pottery and the ease with which it was made and decorated with impressed and moulded details meant that it was very popular. Often Bargeware pieces are impressed with dates and messages and were frequently given as gifts for weddings or other occasions. Maybe the twee messages appealed to Max and Agatha’s sense of humour? With the collection comprising nearly 50 separate pieces, Max certainly found great interest in them.

Rosalind and Anthony

Agatha’s daughter Rosalind and her husband Anthony spent a lot of time at Greenway. They looked after it whenever Agatha was abroad or at another of her houses, increasingly focussing on the garden which needed to turn a commercial profit. Agatha officially sold Greenway to Rosalind in 1959 but she moved in fully only after Agatha and Max’s deaths (1976 and 1978.) Like her mother and grandparents before her, Rosalind was also an avid collector though her new husband was equally prolific, if not more so.

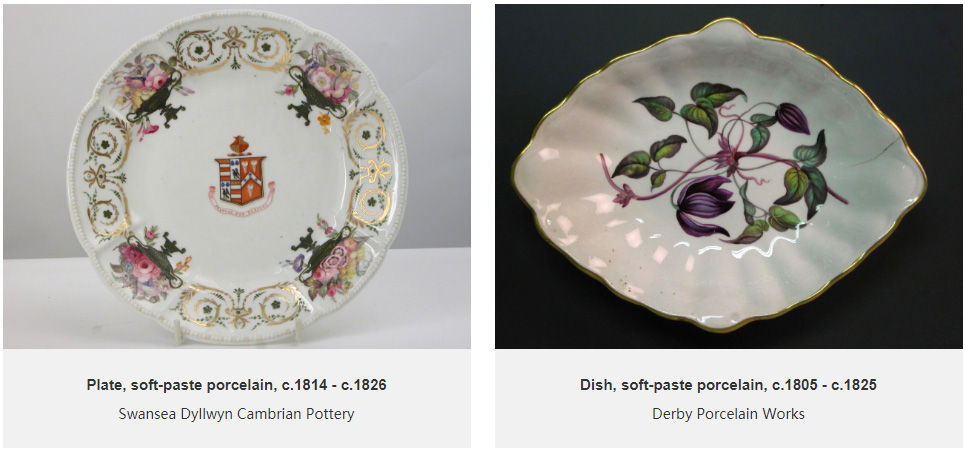

Much as Agatha had bought her grandparents’ china to Greenway, so Anthony bought his parents’ collection of Swansea and Nantgarw porcelain when they sold their Welsh house Pwllywrach. Over 100 individual pieces are still in the collection today. Amongst these are a large number of early 19th-century pieces with delicate floral decoration, some from specific botanical series. These seemed to appeal particularly to Anthony, perhaps because of his interest in gardening, and he supplemented his parents’ collection with new pieces of late 18th- and early 19th-century Derby porcelain, also with botanical decoration. Many of these items are marked with the pattern number or botanical name hand-painted on the reverse. Derby copied specimens from William Curtis's Botanical Magazine (printed from 1787) and intended these wares to be used mainly for dessert, for which allusions to flowers and fruit were appropriate. After 1967, Anthony had added to the collection so significantly that two niches were created in the Morning Room to display this growing collection.

Studio Pottery

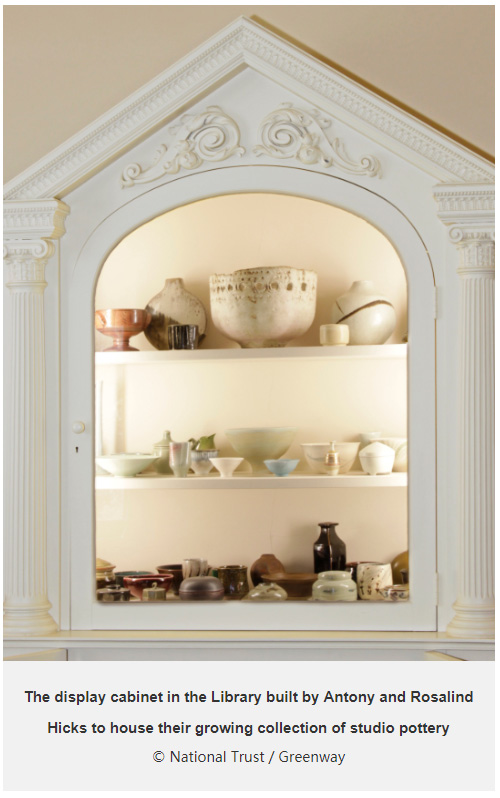

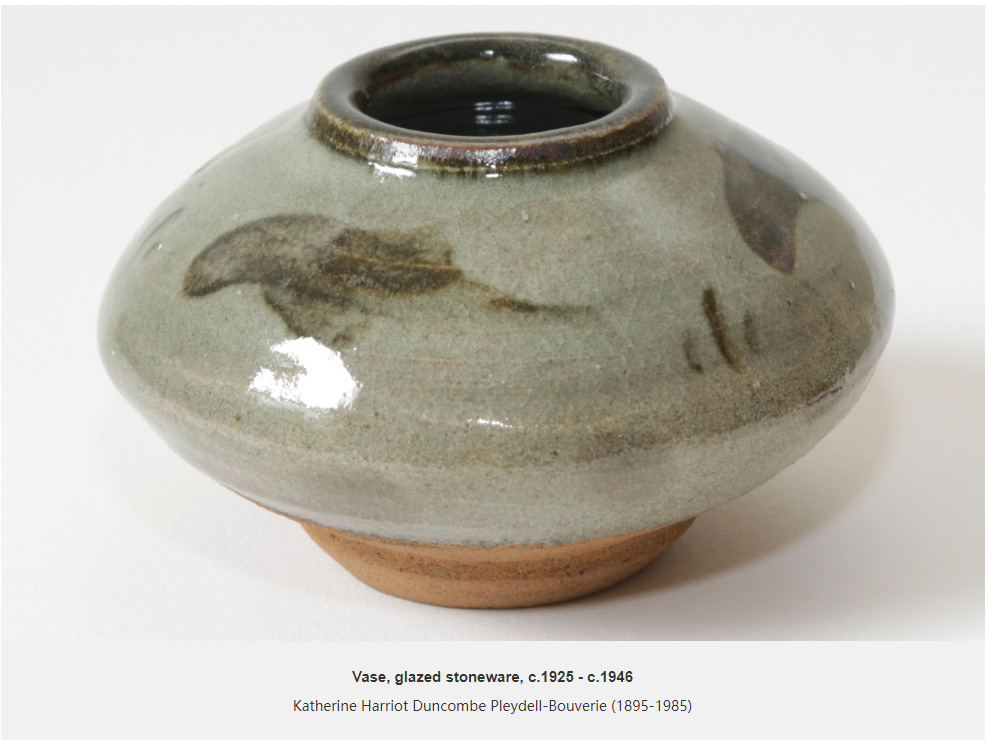

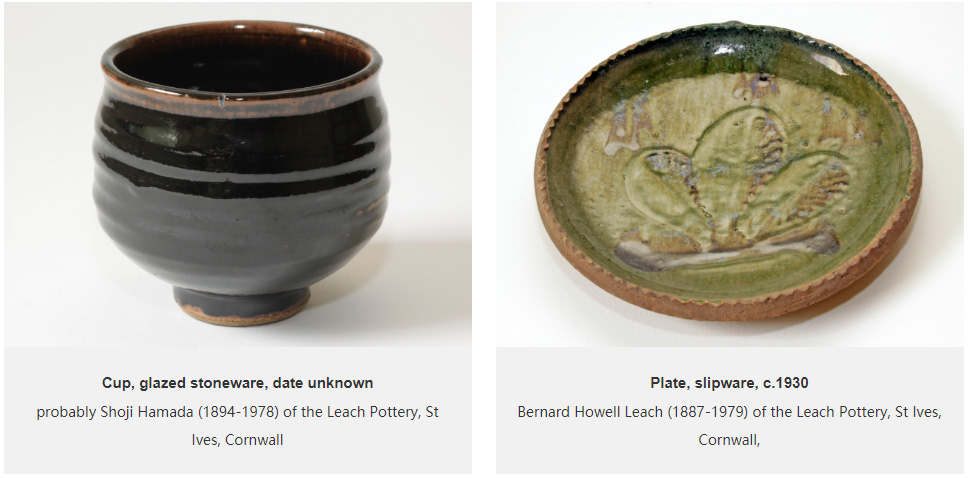

The latest addition to the ceramics collection at Greenway – but perhaps the most significant – is the studio pottery. Consisting of over 100 pieces, it forms the largest modern studio pottery collection in the National Trust. The collection was entirely amassed by Anthony and Rosalind, not inherited, and as such is also still in situ in the place for which it was intended. Little is known about how Anthony and Rosalind went about acquiring this collection but evidence suggests, though they both were interested, Anthony was the driver. For a couple with a predisposition towards collecting and disposable income, combined with their location in the South West with its tradition for studio pottery and their proximity to potters of repute, it isn’t surprising that Rosalind and Anthony built such a collection.

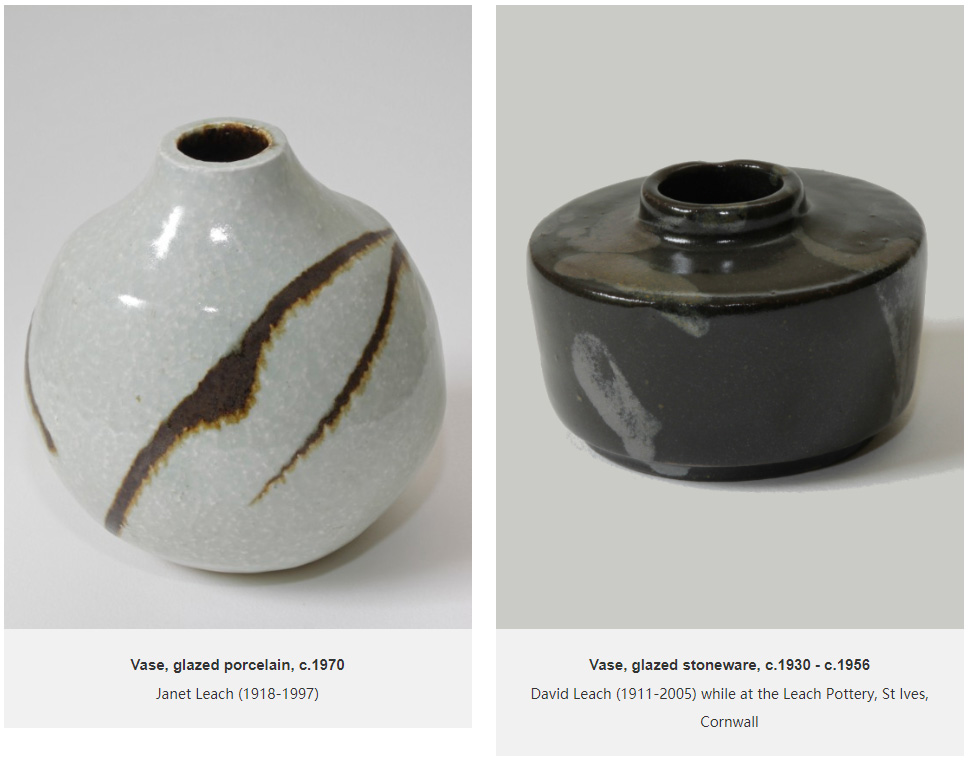

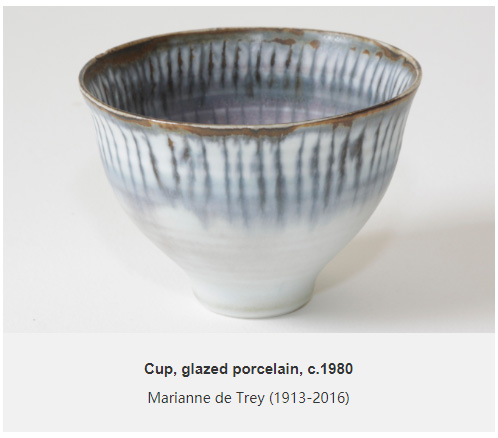

As with most studio pottery collections, the Leach name features heavily. Bernard Leach (1887-1979) is considered the ‘father of studio pottery,’ and was based from St Ives where, along with Shoji Hamada (1894-1978), they spearheaded a new type of pottery that blended the tradition of English wares with the influence of Japanese and Eastern styles. For Leach, pottery went beyond simply making – it was a way of life, blending art, philosophy, design and craft. Leach’s concept of ‘honest pots’ perhaps appealed to Anthony who studied at the School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS) and was fascinated with the Far East and Buddhism. Greenway’s collection features pieces by Bernard as well as his wife Janet (1918-1997) and also his son David (1911-2005) and grandson, Jeremy (b.1941) who both worked at Lowerdown pottery, only 20 miles from Greenway in Bovey Tracey. Marianne de Trey (1913 - 2016) is another featured potter with a local connection. She was based at Shinner’s bridge at Dartington (formerly Leach’s pottery) which became integral to the Dartington arts programme established by Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst.

The spread of local potters represented in the collection and the dates of these pieces – collected mostly between the 1970s and 1990s – suggests that the Hicks were buying new pots directly from the potters themselves. They undoubtedly would have visited local exhibitions and perhaps purchased from key galleries including the Devon Guild of Craftsmen (who represented de Trey) at Bovey Tracey. The large pot by Ken Butler was purchased from a gallery in nearby Totnes; the card for ‘Folkcrafts Ltd’ is still inside.

In 1982, the Hicks’ additions to Greenway’s collections were such that they needed yet more storage. New bookcases were installed in the library as well as a dedicated cabinet for the studio pottery collection. Perhaps conscious of lack of space – or a tight budget – the studio pottery purchases were never normally large; small scale pots, bowls or dishes are the norm.

Notable exceptions to this are a slipware dish by Svend Bayer (b.1946) and a beautifully sgraffitoed Michael Cardew Gwari dish. As a familiar Greenway quirk, this dish still sits partially hidden beneath a selection of hats in the entrance hall, just as it did when the family lived there.

The quality of the collection varies. Roughly a third is still unattributed, although research is ongoing. Many pieces are decidedly ordinary and perhaps represent opportune rather than planned purchases. Accounts from the Hicks’ housekeeper of the late 1990s suggests that Rosalind often bought artworks because she wanted to encourage the artist and that she was less concerned by artistic merit. This might account for the varying quality and number of unrecorded makers that are represented. Rosalind and Anthony were certainly interested in understanding materials and pottery techniques. They took evening classes themselves and a pot produced by each of them is still at Greenway though they met with varying success; the green glaze on Anthony’s led it to be dubbed by the family as the ‘vomit plate’.

Some of the pieces however, are evidence of a good knowledge of studio pottery and an eye for a good pot. Amongst the collection are some of the key names of the studio pottery movement, from the South West and beyond: Shoji Hamada, Lucie Rie (1902-1995), Norah Braden (1901-2001), Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie (1895-1985) and William Staite Murray (1881-1962). Pieces by these potters may represent a concerted effort by the Hickses to adopt a ‘one of each’ approach to acquiring examples by the key names of the studio pottery movement. These items were almost certainly bought through dealers or at sales; the Hamada pot still retains its auction label. Interestingly, it is the examples amongst these names that constitute the earlier items in the collection, dating to the 1930s. The piece by Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie dates to between 1925 and 1946 when she was based at the Cole Pottery, Coleshill, Wiltshire. One of the Bernard Leach pieces – a slipware plate - is also an earlier example from the St Ives pottery, dating to the 1930s.

The beauty of Greenway’s ceramic collection is truly in its whole; multiple layers of family collecting can be viewed individually but come together to make a complete story, giving visitors an insight into the lives and consumerist habits of an upper middle class family, punctuated by some rare and fascinating pieces.

Notes

[1] Agatha Christie, An Autobiography, 1977, p.69.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Agatha Christie, The Mysterious Mr Quinn, 1930.

[4] Max Mallowan, Mallowan’s Memoirs, 1977, p.14.

[5] Henrietta McCall, The Life of Max Mallowan: Archaeology and Agatha Christie, 2001, p.184.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Laura Murray, Senior House Steward at Greenway, and Christopher Woodman, volunteer photographer for the National Trust, for their help in photographing some of the objects that appear in this article.

About the author

Alison Cooper is Curator for the National Trust in the South West covering properties in the Tamar Valley and English Riviera including Cotehele, Antony, Buckland Abbey, Coleton Fishacre, Greenway and Saltram. Previously, Alison was Assistant Curator of Art and then Curator of Decorative Art at Plymouth City Museum & Art Gallery where she developed an interest in 18th-century collections with a specialism in ceramics.

02 Apr 2019