Chinese export porcelain production and trade have a long history. Silk, tea, and ceramics are the three major commodities on the ancient silk road. While silk and tea are consumables, ceramics can survive and spread.

From the end of Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) to the middle of Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), Jingdezhen, known as the "Porcelain Capital" because it has been producing pottery for years, became the main area for producing China's export porcelain. Its porcelain began to be sold to European and American markets on a large scale, gradually becoming a "world commodity" involved in the process of globalization.

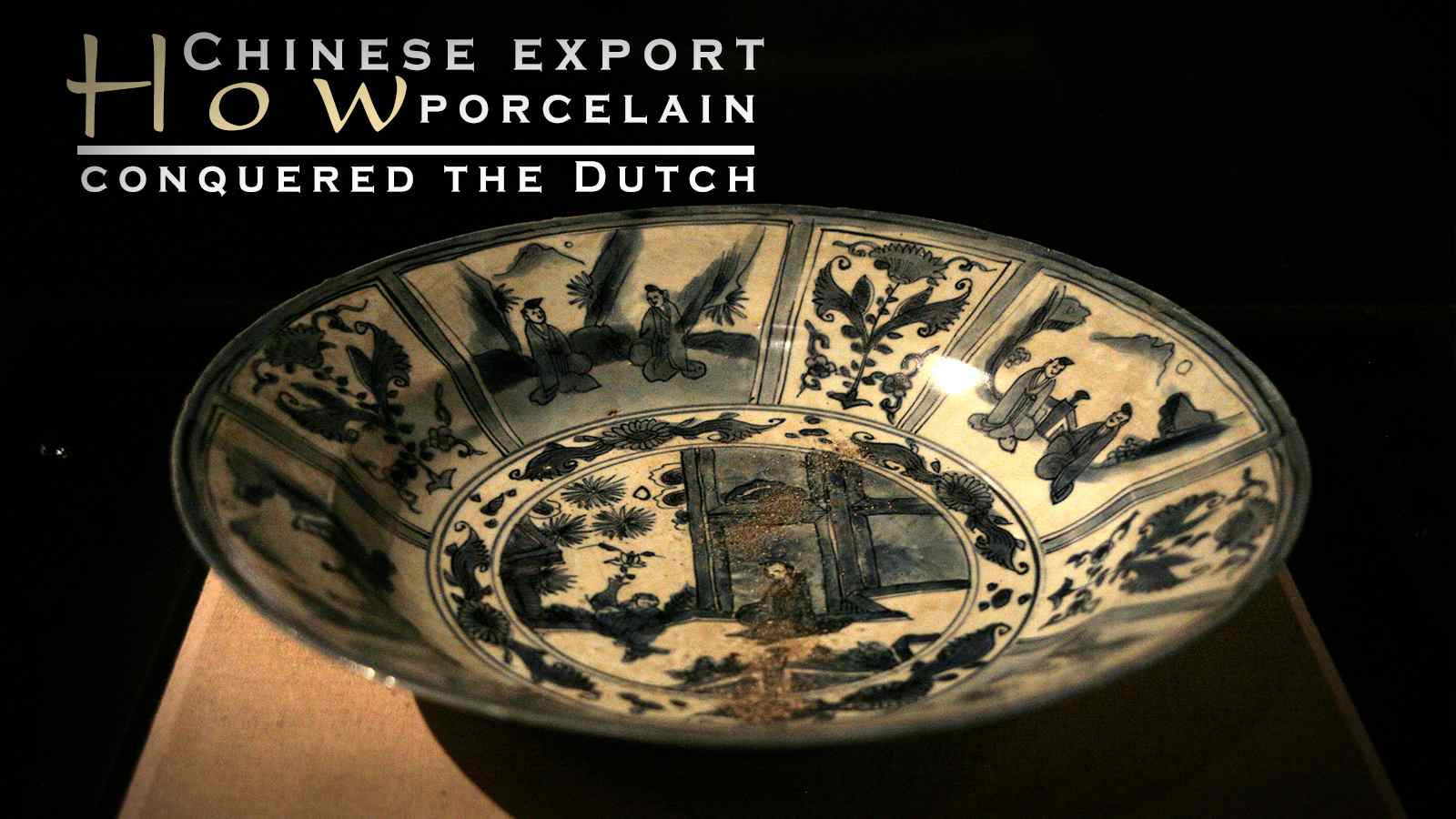

A Chinese export porcelain exhibition at Nanshan Museum, Shenzhen, January 31, 2018. /VCG Photo

In 2007, a large amount of "Kraak ware" was salvaged from the sunken "Nan'ao-1 ancient ship" that originated around the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties, which once again focused public attention on this kind of Chinese ceramics that had once been sold abroad.

What is Kraak ware?

Kraak ware is a type of Chinese export porcelain produced mainly from the period of the Wanli (1573-1620) emperor during the Ming Dynasty, but also from the eras of the emperors Tianqi (1620-1627) and Chongzhen (1627-1644) as well.

In the 17th century, two merchant ships, "The Santa Catharina" and "Carrack" in Portugal, were intercepted by the Dutch East India Company, carrying mostly Wanli porcelain.

A Chinese export porcelain exhibition at Nanshan Museum, Shenzhen, January 31, 2018. /VCG Photo

This porcelain was sent to Middelburg and Amsterdam in the Netherlands to be auctioned, where they made huge profits. This "trade incident" caused a stir in Europe and greatly stimulated the desire of the Dutch East India Company to deal with Chinese goods, especially its porcelain.

No one could give the origin or exact name of this porcelain, which was called "Kraak ware" because they had been seized from a merchant ship named "Carrack."

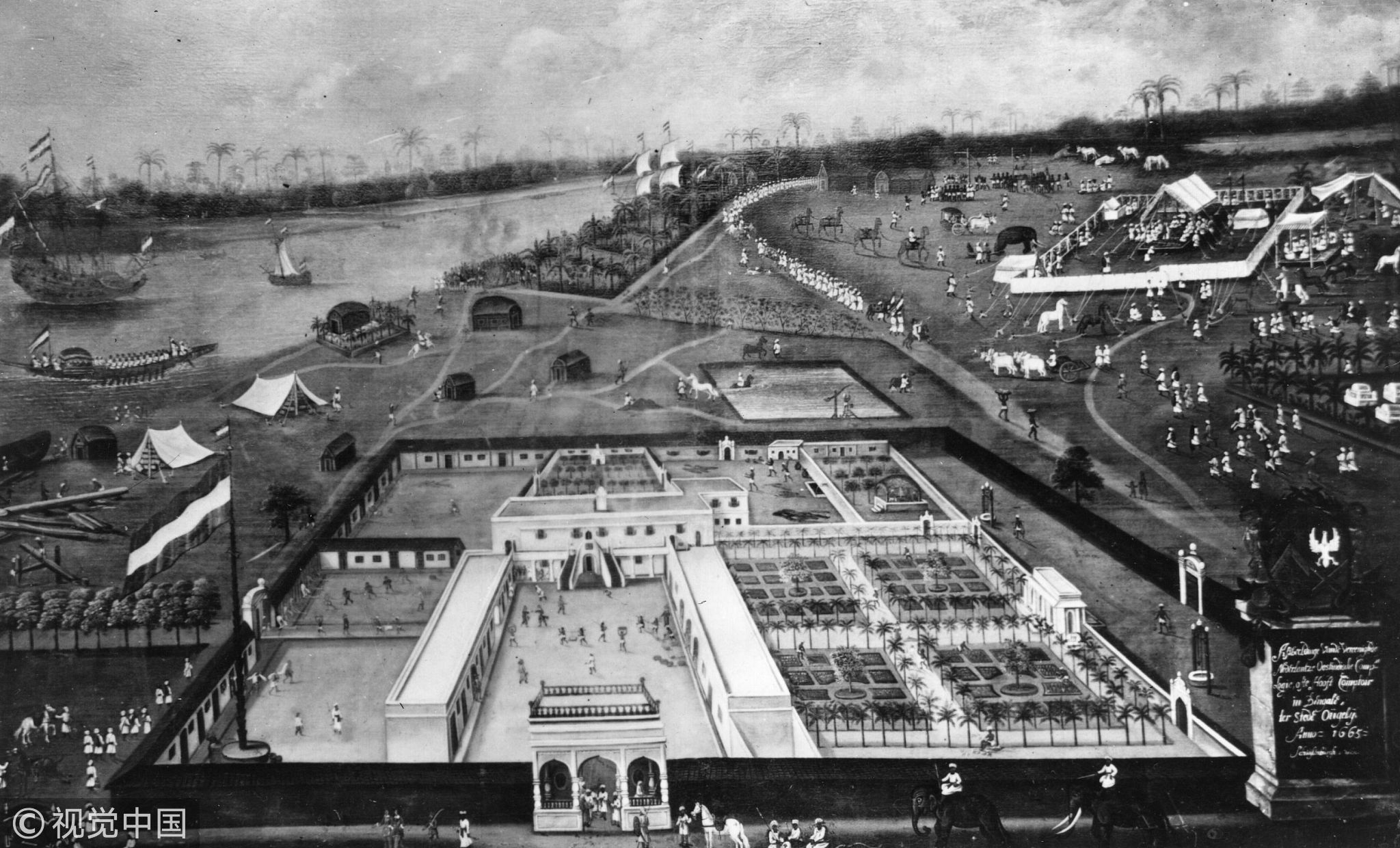

Circa 1665, The central offices of the Dutch East India Company at Hugli, in Bengal. /VCG Photo

The name's origin has long been a subject of debate. Some scholars think it came from a Portuguese merchant ship called "Carrack," which the Dutch call "Kraken." Others insist it is taken from the Dutch word "Kraken," which means fragile.

The messenger of eastern and western civilization

No matter where the name comes from, the export of Kraak ware promoted the further development and prosperity of the Chinese porcelain industry. As a cultural messenger, it spread Chinese culture and further influenced the transformation of European art from Baroque to Rococo style.

A Chinese export porcelain teapot in the exhibition at the National Museum of China, May 13, 2017. /VCG Photo

On the other hand, Europeans' love for Kraak ware and the huge profits brought by it led to its imitation in Portugal, Netherlands, Germany, Britain and ancient Persia. Such large-scale imitation promoted the development of European ceramic industry and eventually produced real porcelain in the West.

The unique global trade goods

As a result of the "Haijin," or sea ban, which was a series of related isolationist Chinese policies restricting private maritime trading and coastal settlement during most of the early Hongwu Emperor from the Ming Dynasty, overseas trade was severely restricted. In 1667, "Haijin" was abolished, China announced its opening to the outside world, and China's commodities such as tea and porcelain were once again allowed to be traded abroad. From the beginning of Wanli emperor during Ming Dynasty, export porcelain began to sell overseas, and became popular among Europeans.

A British Royal Worcester Wucai plate (1775-1780) from the British Museum, which exhibited at National Museum of China, December 6, 2012. /VCG Photo

In the 17th century, Netherlands replaced Portugal as the monopoly manufacturer of Chinese export porcelain. From 1602 to 1682, at least 16 million pieces of Chinese export porcelain were transported around the world by Dutch merchant ships.

Dutch merchants opened up the market for Chinese porcelain in Europe.

They built a procurement network and had successful control and deployment methods in the porcelain's quantity, style, sales price, and shipments.

A set of Chinese export porcelain in the exhibition at the National Museum of China, May 13, 2017. /VCG Photo

For example, the merchants first brought the models made from utensils used by Europeans to Guangzhou and invited Chinese porcelain artisans to copy them and then sell them back, resulting in unprecedented success.

Since the patterns and design can be customized, porcelain was introduced and beloved by ordinary families in Europe.

The price of "Kraak ware" has declined in the European market since it became an important commodity for the Dutch East India Company, and the middle class and the general public can own this kind of Oriental porcelain from afar as well.

Although "Kraak ware" was no longer a luxury enjoyed only by the royal family, Europeans love for it continued to grow. This special trade continued until the time of the emperors Yongzheng (1722 - 1735) and Qianlong (1735 - 1796) in the Qing Dynasty.

"In the thirty-ninth year of Qianlong period, the Dutch East India Company sent nearly 400,000 pieces of porcelain to Britain," said Christiaan Jan Adriaan Jorg, Professor emeritus from the Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society, in an interview with Xinhua News Agency.

"Among them, there should be no less Kraak ware."

(Top image by Xu Qianyun)